If there’s nothing us writers like more than reading a great book, it’s seeing how that book came to be. Lucky for us, we got exactly that when Rowling released a snippet of her outline for the fifth Potter book, Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix.

Problems with Order of the Phoenix

First, let me say that Book Five is my least favorite of the bunch. It’s an 870-page beast with a number of redundant scenes (like when Harry is either dreaming or arguing). Even Rowling wishes it had been better edited.

Still, the book deserves praise, especially considering its intricate plot and the abundance of characters (and all written on a tight deadline). Stephen King said he liked the fifth book “quite a bit better” than the previous four, and added,”Harry will take his place with Alice, Huck, Frodo, and Dorothy, and this is one series not just for the decade, but for the ages.”

In recent posts, we saw how Rowling’s plot for the Sorcerer’s Stone hit all of the structural milestones necessary for a tight-knit novel. But now the question is, how exactly did Rowling develop her story idea into seven weighty books?

For this post, I’ll be drawing solely from Stuart Horwitz’s groundbreaking book, Blueprint Your Bestseller: Organize and Revise Any Manuscript with the Book Architecture Method.

Don’t Say “Plot”

Ironically, I frequently used the word plot in my last post, but now plot is a four-letter word. Horwitz explains why he dislikes the word so much, and I have to say, I agree with him.

For one thing, [plot] is a term with nearly unlimited associations. It’s hard to get anybody to focus on what is actually going on in their book while they are worried about whether their plot is good. For another thing, plot is singular, as if it somehow references everything. As such, you can’t work with a plot.

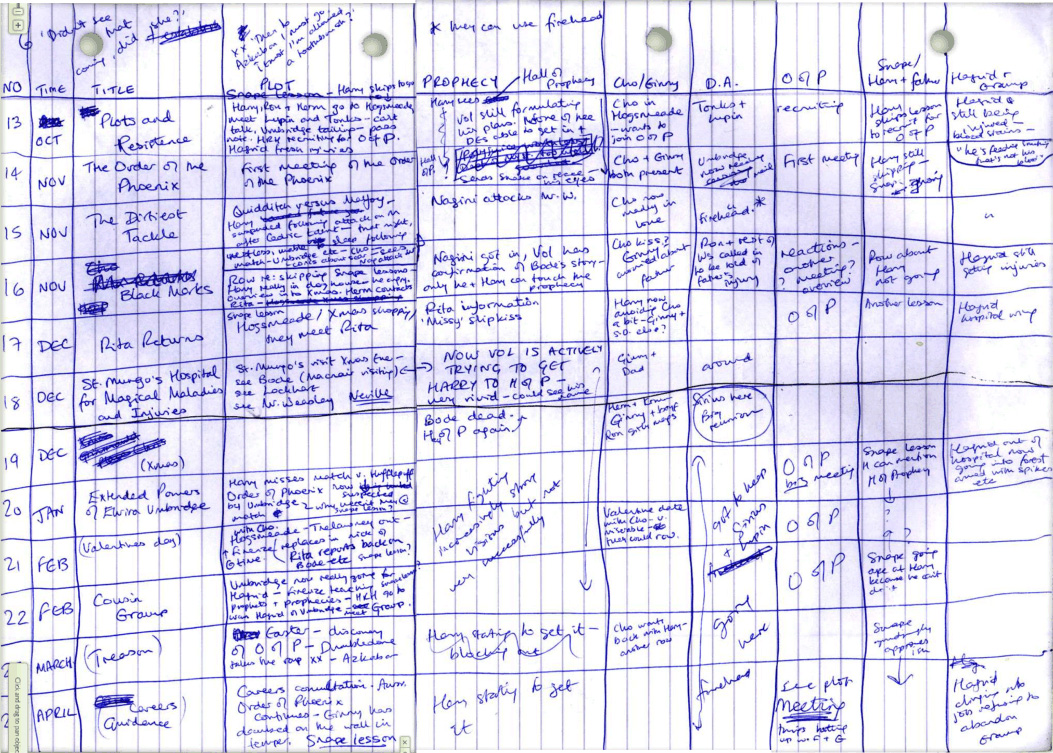

Rowling obviously agrees with Horwitz, because look at how she structures her outline for Order of the Phoenix. (You can enlarge my transcription below by clicking on it. I cleaned up the outline by writing out abbreviations and completing sentences.)

Series: The Real Plot

Series is what Horwitz says should replace plot (and sorry, the plural of series is series). Although Rowling uses the word plot, notice her outline isn’t simply one chaotic column that’s trying to track everything. Instead, she divides the action into six columns of individual series:

1. The Hall of Prophecy

2. Harry’s feelings for Cho versus Ginny

3. The creation of Dumbledore’s Army

4. The creation of Order of the Phoenix

5. Harry’s relationship with Snape

6. And the mystery of Hagrid’s half-brother, Grawp

The end result is an engagingly complex novel—not because Rowling has one twisty-turny plot, but because, as Horwitz says, she breaks down her story into “clear, meaningful series that intersect and interact in unusual and consequential ways.”

It’s actually quite simple what’s going on in Order of the Phoenix: A teenage boy is trying to juggle his school work, his friends, his enemies, and his first romantic relationship. But Rowling has these series collide with each other in surprising ways to create a feeling of complexity. As Horwitz says:

How you handle your series will determine your readers’ forward progress and their level of commitment to your work. Series is how people become characters, how objects become symbols, and how a message repeated becomes the moral of your story.

In my next post, we’ll look at exactly how Rowling brings these series to life.

For more posts on Rowling’s Outline and the Book Architecture Method:

How Rowling Formed Her Narrative Arc (Rowling’s Outline and the Book Architecture Method, Pt II)

How Rowling Created Key Scenes (Rowling’s Outline and the Book Architecture Method, Pt III)

Wow, fascinating, and great tips! Thank you for sharing!

~Aspen

LikeLike

Thanks for the encouragement, Aspen! (Writers can never get enough of that). Hope to hear from you again soon.

LikeLike

Argh!!! I had a feeling I would have to plot EVERY SINGLE ONE of my “series” individually–but I hadn`t considered interconnecting them ( aha!). Just so I understand this correctly. SERIES is what other would call PLOT THREADS, or THROUGHTLINES? Or are they SUB PLOTS intertwined around one main plot that is usually the ACTION plot that moves the story forward. I don`t know why I even bother…I should just go write.

LikeLike

I know how you feel, Claudia! Yes, generally speaking, “series,” “plot threads,” and all the rest of those phrases mean the same thing. If you notice in Rowling’s outline, she has one column that’s simply labeled “plot,” which, like you said, is her main “action” series that keeps all of the smaller series on track. Hopefully sometime in the near future I’ll publish a post about how to determine what should be your main series in any given story. Happy writing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi there! In my book I call that main action series the central series — I think series is a helpful distinction because as CS says we are trying to weave series together in interesting and consequential ways… And events aren’t any different from character development, relationship conflict, symbols, locales or any other narrative element. (And Claudia, you really only have to track 12-15 series!)

LikeLike

From the author himself. Thanks for the clarification, Stuart, and thanks for dropping by!

LikeLike

Thank you so much for answering my post, Stuart. I feel honored. And a big thank you to CS also. This is why I love this place so much! So many wonderful people coming together to share their knowledge. Thanks for this space. A question for Stuart. Why do you say that I only have to track 12-15 series? Is that the magic number for novels? Or is that JKR`s magic number?

LikeLike

I LOVE the theme of your blog- fun, informative, and generous.

LikeLike

I woke up with a cold this morning and really needed a pick-me-up – thanks for making my day, Diahann!

LikeLike

I just came back to read this an it was like magic. It was as if I hadn´t read it closely before and now the magic was opening up to me. People become characters, objects become messages, messages become the moral of the story…mind blowing!

LikeLike

That’s been my experience, Claudia — tracking more than 18 can be a little self-defeating, while less than ten can make the overall texture a little thin. Look for more responses from me on this site in the coming days!

LikeLike

Thanks again! And by the way, last night I did this little exercise and came up with 12 series for my Middle Grade novel–so far. It´s interesting how doing this you end up catching plotting mistakes, and you realize that in order for something to work at the climax, you need to give some info beforehand. Today I`m going to try and make them come together at important moments and i`m going to try my hand at suspense, surprise and shock! Thank you Stuart!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good job, Claudia – keep hacking away at those WIP’s!

LikeLike

Thanks Carolyn. And I hope you’ve had time to do some plotting of your own.

LikeLike

Thank you. Thank you. Thank You.

I have a number of plot-series ideas, and I wasn’t sure how to assemble the puzzle, to find a way that works best for me. Plus, I was using the HP series for my benchmark for quality.

Now I can actually do what I have determined I want to do.

Thank you for your brain, your ability to observe, to analyze and to articulate what you have figured out!

LikeLike

Thank you, Kathy – what a wonderful way to start a Monday morning. Best of luck on your writing and hope to hear from you again soon!

LikeLike

A little late to the game here. I’m currently reading/using Horwitz’s book and am having some trouble applying it to my novel. (disclaimer: haven’t read Harry Potter yet; waiting for children to be ready)

I had understood “series” to mean something more like “themes” (not to be confused with how Horwitz uses “theme,” as in that one thing your book is about). It’s helpful to think of series as a subplot/side-plot. But it also confuses me more.

Let me explain. My book is about someone who, because of events in past, clings to predictability in life, but also wants out of it. She enters an environment that’s all about shunning tradition, having fun and being unpredictable, where she falls for a man who is the epitome of this environment . While trying to pin him down, she watches him unravel. In the process she begins to lose control of herself. (clearly I still have to work on pitch, but I’ve yet to tease out EXACTLY what book is really about. Enter Horwitz).

So, I’d thought of these as being series:

Control

Losing control

Surrendering/letting go (ugh, I had this going way before Elsa), meaning: not self conscious.

Chaos

Self Determination

Routine/scheduling/pattern/predictability

Losing yourself

Knowing who you are/where you are in life

Zeitgeist (an environment that encourages chaos and do-whatever.)

But hese in and of themselves are not plot points. They are the “themes” which the action revolves around.

So:

Is chaos a series? Is losing control a series? Or is chaos the series and losing control an element in the series? In other words, does that count as one or two series?

Letting go series? Or is having fun (a way of letting go) a series? Is booze and drugs (a way of letting go) a series? Is enjoying yourself a series? Or are the latter three elements in the “Letting go” series.

What about self determination? Having all that fun is about shunning tradition and doing what YOU want. So do fun/booze/drugs/enjoyment fall under “self determination “series?

Is Schedule/routine/pattern a series, or would that be part of the “control” series.

Is my main unpredictable character a series and the character who relies on routine a series?

I realize this is probably very confusing to read, but I am very confused myself. I don’t know if I have over twenty series or if I have 12 solid ones that incorporate these other elements. I really like Horwitz’s book because it’s a method and not a recipe with specific ingredients (those seem to me to help produce formulaic books). But because it’s a method, it’s elusive. I haven’t found any discussions on this on other blogs, or on whichever forums I’ve thought of (leaving me to learn from post on Harry Potter, a book I’ve not read).

I really wish Horwitz had a forum on his own website, where he might pop in from time to time 🙂

Terribly sorry for my longer-than-blogpost comment but I’m quite stuck. Thanks much for any advice/thoughts.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, Mae, you may very well have come to the right place!

I say this because C.S. and I are currently collaborating on a chapter for my second book, due out in January, which is *all about series.* It turns out that there is more to know about this concept, and that knowing these intricacies helps a writer immeasurably.

But not to give that to you as the only answer. Here’s the thing: for series to work they have to be represented concretely. Otherwise it’s not a novel or a memoir — it’s a tract.

So when you start talking zeitgeist and chaos, you lose me. When you start talking about a schedule, hopefully represented by something concrete like a calendar, or drugs, hopefully represented by a certain drug, then we can see things repeat and vary, we can see the change in the series.

And yes it will add up to something more than just a calendar or a drug, but first it has to be those things because series are there to help you show not tell.

Feel free to email me through my website with more advanced questions, and definitely check back here as well because C.S. has got this writing theory stuff dialed down.

Otherwise I wouldn’t have brought her on as a co-author!

LikeLike

Is it possible that you are missing the blindingly obvious, Mae? It might help to see these points as a series of sub-plots – plot arcs that belong to and are worked through a theme (falling out of the spirit of the time and finding it again).

Having Control > having it tested > failing the tests > surrendering > losing control > losing yourself > falling out of the spirit of the age or spirit of the time your hero is in (the zeitgeist).

Losing yourself > experiencing chaos > gaining some self determination by using techniques to establish routines

Using those routines to establish predictability in your hero’s life > self determining behaviours > finding yourself > moving back into the Zeitgeist (spirit of the age or spirit of the time) – the thought that typifies and influences the culture of a particular period in time.

It is a story arc, not a stochastic list – and a damned interesting story arc to boot.

Go for it – you are onto something here.

LikeLike

Forgot to mention – it falls naturally into three Acts.

LikeLike

I just wanted to thank you for this post. This has greatly helped jump-start my editing process (if only I had read this before I wrote my manuscript my brain would not feel so mushy!) when I was feeling overwhelmed by the various plot/subplot threads running through my story. Great post and great website. Thanks from this writer!

LikeLike

I’m so glad that this post was helpful to you, Carrie! And thank you for taking the time to let me know—I love hearing from other writers!

LikeLike